Albert Einstein taught himself the violin and would play duets with Max Planck, fellow Nobel Prize winner and the “Father of Quantum Theory,” on piano. Marie Curie rode her bicycle to clear her mind and relax. And Erwin Schrodinger – of Schrodinger’s cat fame – crafted dollhouse furniture.

Outside the Lab is a new Research Frontiers blog series that highlights our faculty’s non-academic pastimes that help keep them focused through creative pursuits.

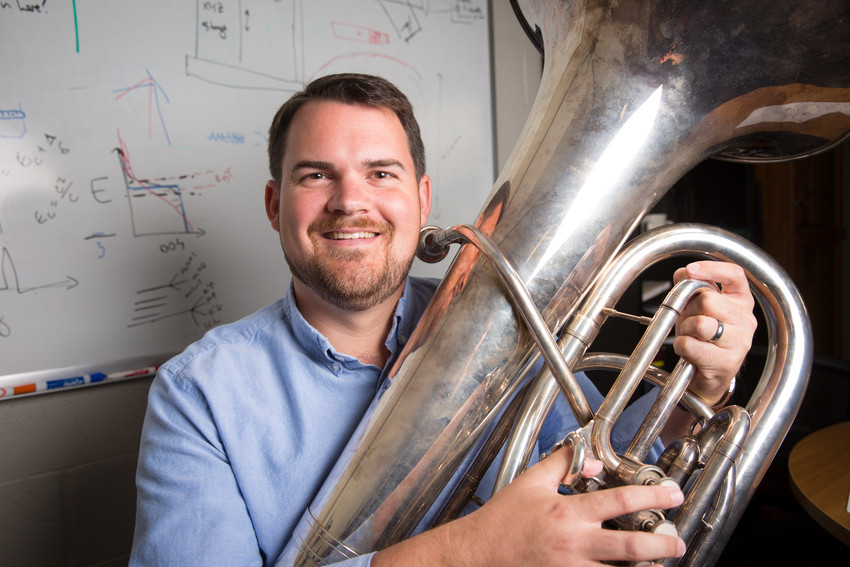

In this post, Hugh Churchill, an assistant professor of physics and an Arkansas native, describes his love of the tuba. Hugh graduated from Oberlin College with a Bachelor of Music and a Bachelor of Arts in physics and mathematics and went on to earn advanced degrees in physics from Harvard University.

Every student in Conway who would be taking band or orchestra the next year got to go to the band room and try out instruments. I was pretty sure a brass instrument was going to be the one, and I started with trumpet and worked my way down. As I went lower, the mouthpieces became larger and less uncomfortable. When I made a sound on the tuba, Lowell Cavender, who would be my tuba teacher until college and is now a band director in Springdale, proclaimed enthusiastically that I was a natural, and I signed up. This is an old band director’s trick to fill out perennially under-staffed tuba sections.

Physicist Hugh Churchill holds a bachelor’s degree in music. | Russell Cothren, University of Arkansas

I find it immensely satisfying to provide a big, fat base onto which all of the other instruments in a band or orchestra can be layered. This is particularly true in an orchestra where there is usually only one tuba player, and I really enjoy the responsibility, and slight terror, of providing that foundation alone. The tuba also tends to be used quite sparingly in orchestral pieces, so tuba players learn to appreciate providing a large impact on a per note basis. Dvořák’s famous 9th symphony, for example, only has 14 notes for the tuba, but they are great notes. This was convenient for me in college: One semester I registered for orchestra and calculus at the same time, played all my parts in the orchestra rehearsals, and barely missed any of the calculus lectures.

Surely my most unusual musical performance was the time I played “Boomer Sooner,” arranged for solo tuba, at my grandmother’s graveside service. This was an appropriate tribute to her memory because she was a devoted alumna of the University of Oklahoma with an interest in band music. Early on in my tuba education, a time of loud honks and snorts, she pointed out that these noises were unacceptable and not cute, and that I needed to practice more. This was important motivation for an activity that evolved over the years from something to fill up my middle school schedule, to a serious hobby, to a career goal, and finally back to a serious, if intermittent, hobby.

About halfway through college I decided on science as a career and gave up the multi-hour daily practice sessions of a serious music student, but I have continued playing as much as I can in various ways: at various Tuba Christmas concerts, in the Harvard graduate student orchestra – including a performance of Ravel’s version of “Pictures at an Exhibition,” which has a really great tuba part – or playing klezmer with my violinist officemate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I’m not sure yet how the tuba will fit into my life at the U of A, but I’m sure it will be there somewhere. One highlight already was getting to hear a recital last fall by Dr. Benjamin Pierce, who is the professor of tuba and euphonium at the U of A, and a truly world-class performer.

Musical training has influenced my research because it really teaches the value of diligence. When learning an instrument or practicing a piece of music, there are obvious improvements that happen on a lot of different timescales from minutes to years, so the reward for diligent effort over time is usually pretty clear. In research, it can be much more difficult to tell when progress is being made, but one has to keep trying new ideas or different approaches. Playing the tuba has probably helped me be a more persistent scientist.

You must be logged in to post a comment.