Researchers at Center for Space and Planetary Sciences Study Other Worlds to Understand Ours

A peerless university laboratory and a rigorous interdisciplinary approach to the study of all things beyond our world make the Arkansas Center for Space and Planetary Sciences a training ground for the next generation of NASA scientists. Roughly half of all graduates from the associated master’s and doctoral programs have moved on to the agency itself, a NASA-related research facility or a private corporation with a NASA contract.

Research at the U of A center is predominantly fundamental. Students operate in an academic setting, rather than a mission-driven NASA lab, so they have the freedom to explore fundamental questions. But when they get to NASA, their ideas circulate. In this regard, space and planetary research at the University of Arkansas influences research and missions at the agency.

“The topic or the work students did for their Ph.D. could be something entirely new to NASA methods,” said Vincent Chevrier, research associate professor at the center. “So, in some ways that can be seen as a service. The students and the university indirectly are informing a research agenda at NASA. NASA doesn’t take our research projects, but we provide students who are competent research scientists who work on the projects NASA is developing. We are creating a new generation of NASA research scientists and probably the people who are going to be involved in developing missions.”

With a two-year, $1.6 million grant from the National Science Foundation, the Arkansas Center for Space and Planetary Sciences opened in the fall of 2000. Initially the center was a joint effort between the U of A and Oklahoma State University intended to create a dedicated group of researchers and facilities to contribute to NASA’s ongoing program of robotic space exploration. (Due to changing institutional priorities, Oklahoma State exited the partnership a few years later.)

“We were just a bunch of faculty with common interests who got together and decided we should try it,” said Larry Roe, professor of mechanical engineering. “Even without Oklahoma State, we had a critical mass of researchers to start a rigorous, interdisciplinary program. Not too long after the center opened, we began putting together the graduate degree programs. And I’ll tell you what, since that time, we’ve attracted spectacularly good students.”

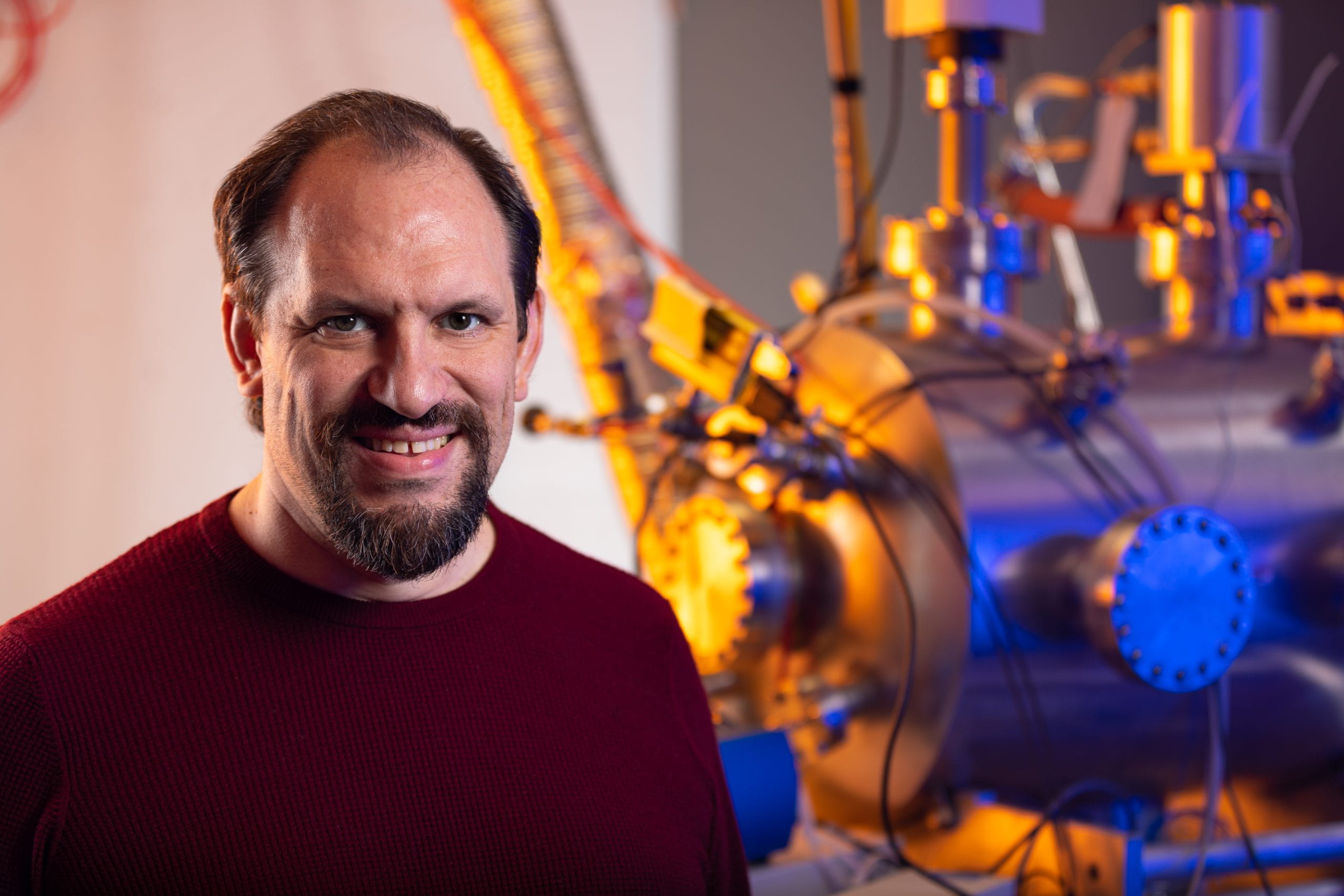

Here since the center’s inception, Roe has served several roles — researcher, teacher, adviser and administrator. He is currently director of the graduate program, and, until recently, for about five years, was director of both the center and degree program.

Roe likes to brag on students and relishes mentioning where alumni are working. While at the U of A, Caitlin Ahrens, currently a NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Goddard Space Flight Center, was named one of the Ten Outstanding Young Americans, an award presented by the Jaycees, for her efforts in science communication and outreach. Other students have earned prestigious internships or fellowships at the National Radio Astronomy Laboratory, the Mars Society’s Devon Island Mars habitat project and the Japanese Space Agency.

As mentioned, about half of all graduates end up working for NASA, directly or indirectly. Including Ahrens, four of the five most recent doctoral alumni, all women, work at NASA — two at Goddard, one at Glenn Research Center and one at the famous Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. The fifth graduate teaches physics at Oklahoma State University.

In all, 45 people have completed the Ph.D. program. In addition to those who have gone on to NASA, 41 percent of these graduates work in academic positions, and 13 percent are in other positions, such as technical management or private business.

High-achieving students and a full-time research faculty member, dedicated solely to the study of space and planetary science, are the primary strengths of the program, Roe said.

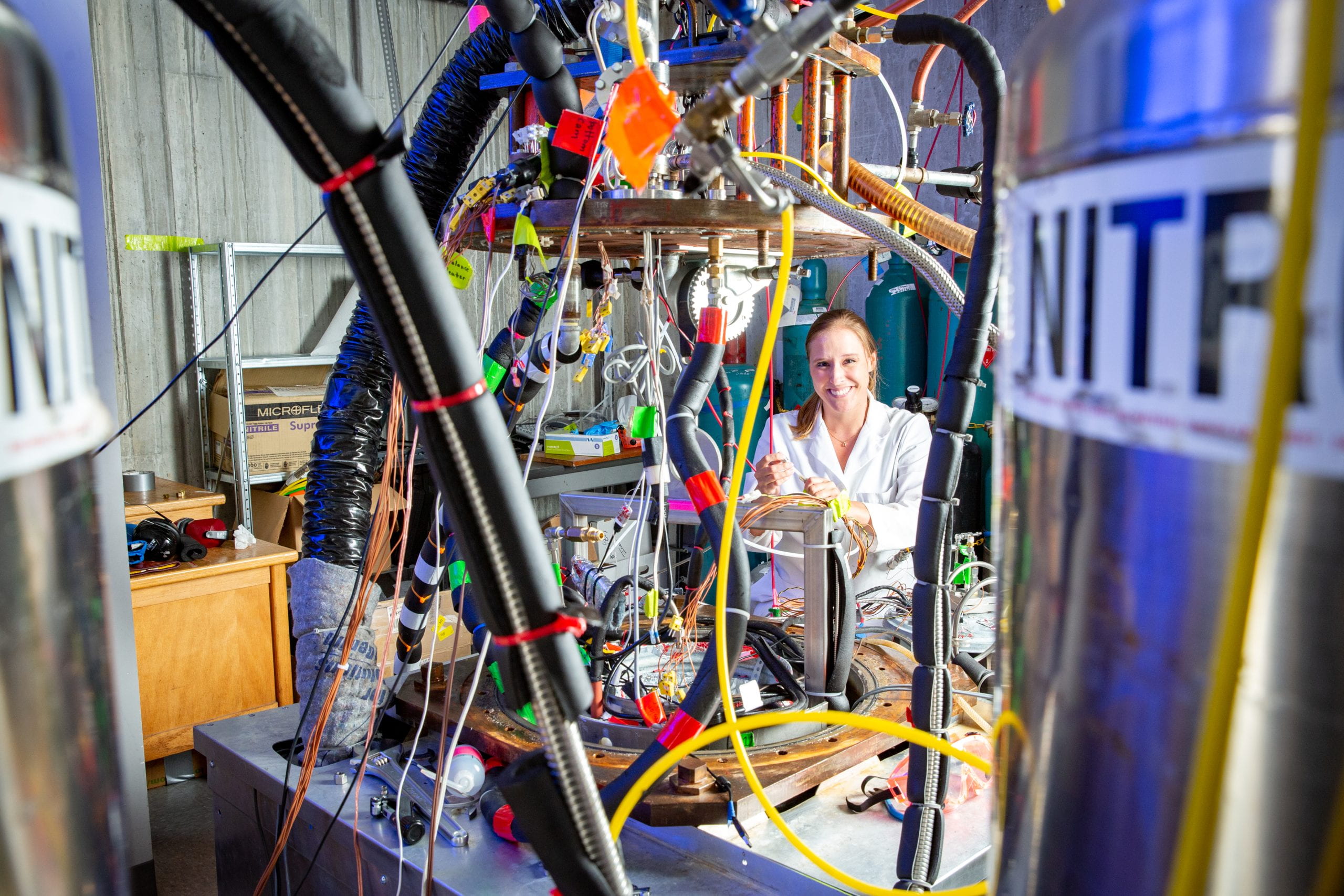

In the Keck lab, researchers build micro worlds that allow them to explore big questions about space and planets, such as why one planet is inhabitable while its virtual twin is not.

Chevrier arrived at the center in 2005, as a post-doctoral fellow at the W. M. Keck Laboratory for Space Simulation, and eventually became a research professor. He has worked as such since 2008, today conducting roughly two-thirds of the center’s research and consistently bringing in about 80 percent of the center funds. This money covers most of his salary, in addition to research expenditures and graduate assistantships.

“Vincent is home-grown, you might say,” Roe said. “The center literally grew him into a prominent scientist in this field.”

All but a pittance of the $8 million in research funding Chevrier has received since 2008 came from NASA, and all students he personally advised became post-doctoral fellows at NASA. Though there are a few drawbacks to his position, it gives Chevrier total freedom to pursue any idea or research project that NASA deems worthy.

“I’m happy with the level of innovation I can have here,” he says. “I can really do whatever I want. At NASA, you can only work on something you’re being paid for. Not here. Here, I have the freedom to develop an entirely new project that may have just popped into my head one evening. I love that system, and I love my lab because, with the help of students and people like Larry Roe, I’ve been able to develop it independently all along.”

Since 2008, Chevrier and his students have worked on several major projects, some of which have guided or influenced NASA missions. Even before NASA confirmed the presence of liquid water on Mars in September 2015, he and other researchers at the center had been analyzing experimental data related to the possible existence of liquid water on the Red Planet. Much of their work since that time has focused on this discovery, expanding it to explore the possibility of viable life on Mars.

Additionally, Chevrier received $320,000 from NASA to study how carbon dioxide ice pits in the polar caps of Mars have formed and evolved over time. The goal is to better understand the seasonal and long-term cycles of these ice pits and how they impact the overall atmospheric dynamics of the planet. More recently, he and two doctoral students published a study showing that water on Mars, in the form of brines, may not be as widespread as previously thought.

Chevrier also received funding to study a possible source of methane on Mars. This could help with future exploration of the planet, as methane can be used as an energy source for robotic or manned exploration.

In addition to Mars, Chevrier and his students have received funding to study the atmosphere of Venus; ice, lakes and liquid hydrocarbons on Titan (Saturn’s largest satellite and the second-largest moon in our solar system); and ices on Pluto.

How, you might wonder, can anyone study ice formation on a dwarf planet 2.6 to 4.67 billion miles from Earth?

The W.M. Keck Laboratory for Planetary Simulations opened in 2004 with a $500,000 challenge grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles to then-center director and chemistry professor Derek Sears. The purpose of the grant was to fund research on the search for water on Mars. Sears already had Keck’s centerpiece in his lab: the Andromeda chamber, acquired from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, when the Center for Space and Planetary Science opened.

The Andromeda chamber was the first stainless steel tube to have a cryogenic chamber inside, where researchers simulated environments and conditions in space. These chambers are as small as a soda can and as tall as a two-story building. Since Sears obtained the first chamber in 2004, the lab has grown; it now has six chambers – one for Venus, two for Mars, one for Titan and two simulating outer regions of the solar system.

Inside these tanks, researchers build micro worlds that enable them to explore big questions, including why one planet is uninhabitable while its virtual twin has all manner of biotic life. They have investigated what Earth was like before the atmosphere contained oxygen, and whether liquid water could exist in a place where it rarely gets above freezing. Researchers study chemical and physical conditions at the surface of planets, how the surface of planets evolved over time, and how they interacted with their atmosphere when it was present.

“The Keck Lab is the biggest university lab entirely dedicated to space and planetary science,” Chevrier said. “NASA has huge space labs, of course, but those are NASA centers, and they’re mission oriented. They’re not a university. I think what we have is special for a university this size. It’s here and not at Stanford or Berkeley.”

Like all other scientific inquiries, people study space because they’re curious, Roe says, “because it’s there. We can observe it, so we want to know more about it, same as a geologist looking at a mountain and asking questions about how it got there or what it’s made of.”

But the Keck Lab facilitates a more applied investigation. It enables Chevrier and other researchers to study other planets so that we might better understand our own. The only way we can understand Earth, he says, is to understand how other planets are similar or different, and how they changed over time. This is especially true now, as Earth is starting to experience significant changes.

“Take Venus,” Chevrier says. “Venus is the same size and composition as Earth. Almost everything is the same, and yet is has a completely different surface and atmosphere. Why? What conditions led to it being 500 degrees Celsius and covered in clouds of sulfuric acid?”

Exploring answers to these questions is important, Chevrier says, because “On Earth, we have the beginning of global warming and runaway greenhouse gases. It’s the very beginning. We don’t know this for sure, but some scientists think that Venus might be an example of an endpoint for these phenomena. If this is true, then understanding what went wrong might somehow help us avoid it on Earth.”