Reducing Rice’s Carbon Footprint

Stuttgart, Ark. — At the edge of Chris Isbell’s rice field, three miles south of Bayou Meto, the famous duck-hunting wetland, Ben Runkle tight-rope walks the narrowest of bridges, a one-by-12 plank spanning two cinderblock towers. He’s proud of the bridge, designed and built it himself, so he and his students can reach the meteorological tower on the other side of the field’s drainage ditch. He’s wearing heavy-duty waterproof boots, hardly the right footwear for the slackline-like sortie, and his arms swing out to maintain balance; Runkle’s trying to get to the tower without falling or looking silly. He manages to avoid both.

The tower, 12-feet tall and supported by tripod sticks, measures everything – the basic, such as air temperature, rainfall, wind speed and relative humidity, and the advanced, including soil nutrients and acidity, water vapor concentration, water evaporation rate, soil moisture and temperature, and, perhaps most importantly, carbon emissions in form of methane and carbon dioxide. Runkle, assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering, has been visiting Isbell Farms once a month, on average, for the past four years. Data gleaned from the tower helps him quantify what Chris Isbell and his son Mark have known anecdotally for years, that their once unique but now internationally renowned method of growing rice significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

“We’re grateful for Ben,” says Mark Isbell, who started working on the farm when he was 13. In addition to putting the numbers behind their sustainable practices, Runkle “keeps us fresh,” says Mark. “He helps generate new ideas and connects us to a different sphere of influence.”

Worldwide Staple

Rice is a staple food for more than 3 billion people worldwide, and Arkansas is the top American producer. According to the Arkansas Farm Bureau, the state produces 200 million bushels a year, grown on more than a million acres. This equals roughly half of all rice grown in the United States, more than Texas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi and Missouri combined. In terms of caloric consumption, Isbell Farms alone feeds 78 million people per day, according to Chris Isbell’s calculations.

As soon as you exit Interstate 40 at Carlisle, 40 miles east of Little Rock and 15 miles north of the Isbells, you can see how most people grow it: Irregular-shaped paddies separated by long squiggly levees, not more than few feet tall. From a crop duster, these levees look like lines on a topo map, which is exactly what they are. Even from ground level, the land only appears flat. (Foreigners swear it is, but Chris Isbell, like everyone else in his family, can spot the subtlest grade.) Instead, on these fields where farmers use the traditional method, or paddies, the land is sloped, or on a grade, as they say down here. The levees serve as dams; farmers use them to flood paddies, and the grade helps move water from one paddy to another.

This method wouldn’t work just anywhere. It’s possible because the soil down here is composed of a dense clay, an impermeable hardpan, as they call it, which functions like a pond liner. It holds the water in place longer than the permeable, sand-based fields closer to the Arkansas and White rivers. It is this impermeable, hardpan clay that makes this area of Arkansas famous for growing rice.

But the traditional method, at least in Arkansas, is fraught with problems. Like all plants, rice loves water, but farmers all over the world are learning their fields don’t need so much of it. In large part, this is due to the Isbells, who discovered that flooding paddies, primarily for weed control, was unsustainable.

In addition to contributing to the depletion of a precious resource, paddy farming comes with a high environmental impact. Worldwide, rice production accounts for roughly 10 percent of humans’ overall methane emissions. Because the soil is deprived of oxygen during flooding, microbes within it produce and emit methane, a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, which is also emitted in high quantities with the traditional method because of the pumps that pull groundwater from aquifers for irrigation.

Zero Grade

Chris’s Isbell’s father Leroy started growing rice here in 1949, and now Chris owns and operates Isbell Farms with his wife Judy, son Mark, nephew Shane and son-in-law Jeremy Jones. On 3,000 acres, they grow long-grain, Sake and other varieties of Japanese rice, including one grain, Koshihikari, which the Japanese thought could not be grown outside Japan.

Leroy, who died in 2014, was curious and ingenious. “My dad never bought a piece of equipment that he didn’t modify somehow to serve us better,” says Chris. In addition to tinkering with and improving implements, Leroy also thought about systems and processes. He questioned conventions, pursued for no reason other than tradition, especially when yields were low or resources waned.

Such as the 1970s, when the water table started to descend. Though few people noticed it, water was going to be a precious resource, much more expensive to irrigate. To save money on pumping, the Isbells – at that time, Leroy, Leroy’s uncle Pete, Chris and Chris’s brother Benny, who was killed in car accident in 1990 – decided to try an experiment. Gradually, they started taking down the levees and leveling the land. This new method allowed water to nourish the plants but removed its herbicide function. Leveling also meant the Isbells and their workers did not have to spend hours walking the levees with shovels, looking for and repairing the breaches that frequently occurred and drained water from paddies prematurely.

These measures succeeded, but the Isbells weren’t finished. Chris remembers the day in 1977 when they decided to go all the way. His father placed a matchstick under a two-by-four, and they watched water run down the board. Any grade, even one-tenth of an inch per 100 feet, caused water to move laterally. They wanted it to move vertically and in one direction, down.

Initially, to level the fields, they had to eye-ball it. This worked okay, but it was inexact. Then land-survey lasers became commercially available, and the guesswork was over. By 1977, Isbell Farms was the first-ever “zero grade” rice farm.

A sample from the field, this dirt clod shows a rice plant sprout and barnyard grass, one of this year’s enemy weeds.

Word spread about the Arkansas rice farmers who’d jettisoned paddies and were still producing high-quality rice. Farmers, researchers and agriculture policymakers from many countries, including Uruguay, Japan, Russia, and Panama, visited Isbell Farms to observe the method, and the Isbells traveled to Costa Rica and Panama to advise rice farmers, including the vice-president of Panama. In following years, upon invitation from the Japanese government, the Isbells traveled to Japan multiple times. (Chris and Judy Isbell have developed many meaningful and long-lasting friendships with Japanese farmers, including one who essentially lived on their farm for several months.) Today, the zero-grade method is practiced all over the world. As an example of its success, the U.S. Department of Agriculture pays rice farmers to level their fields.

“People thought we were crazy,” says Chris Isbell.

But they didn’t understand how the Isbells worked. The zero-grade approach, as with so many other Isbell Farms’s innovations and best practices, came to them after much experimentation. Even before they started leveling, the Isbells had played around with flat areas – to this day, Chris Isbell maintains a four-acre experimental plot adjacent to his and Judy’s house – and noticed they’d probably work. Sure, Leroy might have had crazy ideas, but that only lumped him in with every other innovator. And, because of their rich experience with rice, the Isbells’ innovations were always calculated risks.

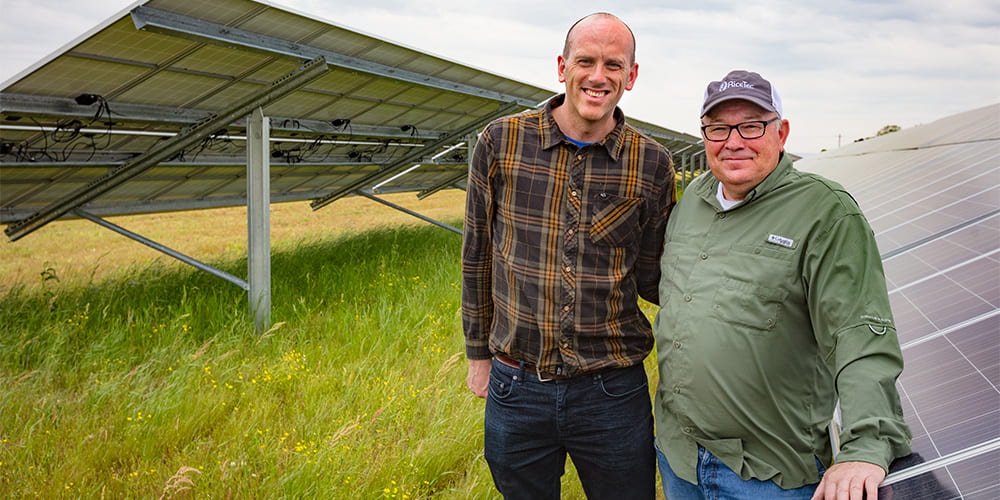

“We’ve always been quick to try new products and technology,” says Chris Isbell, standing with Ben Runkle at an array of solar panels on Isbell Farms.

Chris Isbell inherited his father’s curiosity, ingenuity and unconventionality, which he passed down to his son Mark. These qualities and others, including a kind of sensible fearlessness, have motivated them to try new ideas, their own and others’. Which explains Isbell Farms’s long tradition of collaborating with researchers and other innovators.

“We never say no to anyone,” Chris says. “Though sometimes we should have.”

A Mutually Beneficial Collaboration

One person they’re glad they said yes to is Runkle. The U of A researcher, who received a National Science Foundation Early Career Development award in 2018 to expand his research on sustainable rice production, opened new doors of opportunity for the Isbells. In addition to putting numbers behind their sustainable methods – that is, the specific amount of methane and carbon dioxide emissions from the Isbell’s operations, compared to those of conventional farms – Runkle helped shepherd Isbell Farms through a new and exciting venture.

In 2017, armed with data provided by Runkle, the Isbells, along with six other rice farms, sold the first-ever carbon offset credits for credibly measured benefits of their sustainable practices. Managed by Terra Global Capital on behalf of Microsoft, and established according to a strict protocol developed by the American Carbon Registry, these carbon credits financially reward farmers for voluntarily adopting conservation management practices and other measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Ben Runkle walks the levee next to the field that hosts his meteorological tower.

But the relationship between farmer and researcher is mutually beneficial. Back at the tower, Runkle hunkers behind a ridiculous cluster of wires leading to a data bank inside a weather-proofed plastic box. After switching out a data card, he pokes his head out of this tangled web and says what’s in it for him: “There’re just so many research questions out here.”

To Runkle, Leroy Isbell’s rice fields are one big laboratory. With assistance from the Early Career award and other funding sources, Runkle, one post-doctoral researcher and several students, graduate and undergraduate, use Isbell Farms and methods to investigate:

· how irrigation strategies allow more microbial activity in unsaturated soils

· how much water is used by the plants in transpiration, and how much evaporates from the surface

· how large fields – those between 40 and 80 acres – have areas with greater or lower methane production due to differences in soil type and rice cover

· and how the offseason use of the fields as flooded duck habitat influences crop growth and greenhouse gas emissions the following year.

These questions, likely to beget others, will keep Runkle and his students busy at Isbell Farms for years to come.